In order to explain exactly what socialism is, and how it works, it is important to first understand what the wealth in our society is, and where it comes from. It is a question of whether or not the people who actually create products of material value get to keep the fruits of their own labor, or even a fair portion of the profits, and the answer is that the lion’s share goes to someone else.

Ordinarily, this wouldn’t be a problem if the system self-regulated and produced livable conditions for the worker – if the “invisible hand” as Adam Smith put it, always succesfully provided social benefits through the actions of an individual driven by profit. The truth is that market interactions and price signals are very effective for regulating exchange itself, but the benefits seldom actually reach the people who created the value behind them in the first place.

What is Capitalism?

Capitalism has many possible definitions, but when socialists use the word “capitalism” we are referring to a system of private ownership in which one person, or a small group of individuals, owns and controls a company’s means of production, and is able to exclude access to them.

These means of production are called “private property” or “capital” and include tools, machinery, raw materials, buildings, real estate, etc. A “capitalist,” therefore, is a person who owns capital.

Think of capitalism as an economic monarchy: The shareholders or owners hand orders down, and they are passed through the chain of command until they get all the way to the bottom to you, the worker.

Value and Where it Comes From

In Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith explained the Labor Theory of Value like this:

“The real price of everything, what everything really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it. What everything is really worth to the man who has acquired it, and who wants to dispose of it or exchange it for something else, is the toil and trouble which it can save to himself, and which it can impose upon other people. What is bought with money or with goods is purchased by labour as much as what we acquire by the toil of our own body. That money or those goods indeed save us this toil. They contain the value of a certain quantity of labour which we exchange for what is supposed at the time to contain the value of an equal quantity. Labour was the first price, the original purchase-money that was paid for all things. It was not by gold or by silver, but by labour, that all the wealth of the world was originally purchased; and its value, to those who possess it, and who want to exchange it for some new productions, is precisely equal to the quantity of labour which it can enable them to purchase or command.“

Socialists like to use the example of a chair. A chair has use-value: Someone can sit on it. It is much preferable to standing, and it’s safe to say that at least one chair can be found in nearly every American home. Use-value is a difficult thing to measure, though. Exactly how urgently is a chair needed? We can sit on the floor if we want. We might lie down instead. Some cultures don’t even use chairs.

Well, we can roughly approximate the use-value of a chair, instead, by seeing how much of something else a person is willing to trade for it. This is called “exchange-value.” A chair’s exchange-value might be worth $20, or 5 yards of raw lumber, or 6 hammers, or 1 peacoat. Simply put, a chair’s exchange-value increases or decreases by the laws of supply and demand.

But why does the chair have an exchange-value at all? For this, we refer to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. It is the “toil and trouble of acquiring it.” If you could walk out of your house, and pluck a chair from a tree, it wouldn’t be worth much. It is precisely because a carpenter has taken raw materials and converted them into a chair through labor input, that it has acquired its value.

In order to build a chair, the carpenter needs wood, a hammer, a saw, and glue. He needs to get these items from someone else who made them, so he buys them for whatever their exchange values are. He then puts all of those items together to build a chair by spending a few hours sawing, hammering, and glueing. By the time he is done, the exchange-value of the chair has increased, and he can now sell it.

If he did nothing to the wood, hammer, saw, or glue and then tried to sell it, its value would have never increased. It would remain the same. So, we know that the value of the labor that he put into building the chair is the difference between the cost of his materials and the amount that he sold it for.

Labor Relations Under Capitalism

To continue with our chair analogy, the capitalist is a person who owns the wood, the hammer, the glue, and the saw that are needed to make the chair. The capitalist hires the carpenter to build a chair, and then he sells the chair for its exchange-value.

With the money he received, he keeps enough to replace the tools and raw materials that went into the chair in order to build another, and is left over with the amount of money equal to the labor that went into producing it.

The capitalist now decides what to do with the remainder of the money, which we call the surplus. First, he must pay the laborer’s wages, then he must keep a remainder of the surplus as profit. Adam Smith, here, considers profit a wage paid to the capitalist for the risk and labor of purchasing and managing the tools, raw material, and labor. But, the fact remains that the laborer did the majority of the actual input that turned the raw material into a chair.

As an experiment to see what the capitalist’s actual labor input is to the end product, let’s supose we left him alone with the wood, glue, hammer, and saw; and see what happens now that he took the risk of purchasing the stock. . . nothing. He needs a carpenter, or nothing will happen.

Even if you consider the capitalist more skilled, better compensated, or more essential to production than the worker, the chair still won’t get built without actual labor input. The capitalist can have a brilliant idea for a chair, and purchase mounds of wood, and take every ounce of “risk” that can be taken, but without employees to build chairs, he will have never increased the exchange-value of whatever he already has in order to be sold for a profit. The mere idea to undertake a venture is not sufficient justification to assume an employer had a greater amount of labor input in a process that simply couldn’t happen without his employees – especially to the extent we see in modern society where some employers receive hundreds of times the compensation that their employees do.

Henry George uses the example of gathering eggs in Progress and Poverty:

“A company hires workers to stay on an island gathering eggs, which are sent to San Francisco every few days to be sold. At the end of the season, the workers are paid a set wage in cash. Now, the owners could pay them a portion of the eggs, as is done in other hatcheries. They probably would, if there were uncertainty about the outcome. But since they know so many eggs will be gathered by so much labor, it is more convenient to pay fixed wages. This cash merely represents the eggs — for the sale of eggs produces the cash to pay the wages. These wages are the product of the labor for which they are paid — just as the eggs would be to workers who gathered them for themselves without the intervention of an employer.

In these cases, we see that wages in money are the same as wages in kind. Is this not true of all cases in which wages are paid for productive labor? Isn’t the fund created by labor really the fund from which wages are paid?”

So the leftover money that the capitalist is taking from the value of the chair that he sold for profit, largely comes from the labor of the worker – who didn’t get it.

Now we look back to the hammer: Someone had to cut down wood, and someone had to mine iron to get the raw materials for the hammer. Someone had to build a road that the raw materials are shipped on. Someone had to build the truck that carried the raw materials to the factory. Finally, a worker at the factory took the raw materials, and converted them into a hammer. None of these items simply popped into existence in the hands of the capitalist: they were purchased with the existing labor of the working class.

This is what Adam Smith means by “labour was the first price, the original purchase-money that was paid for all things.”

In capitalism, people who are already wealthy start off by having the money to purchase and control capital. The barrier to entry in production, and their exposure to risk is reduced compared to a person who owns nothing and has no choice but to sell their labor in order to live. When a capitalist is allowed to take surplus value from the labor that his employees as a whole produce, and make decisions with it, he is compelled to make choices that benefit himself. This doesn’t mean that capitalists are bad people. It is their job to increase profits however they can.

Adam Smith hoped that an employer would realize that having well-paid, happy employees would be to his or her own benefit. The opposite is true. Employers have an incentive to suppress wages, cheapen production, deprive workers of benefits wherever possible, and automate their own workforce out of the job. This was verified strikingly in the deplorable working conditions of the industrial revolution.

From a classical liberal perspective, this is the beauty of the free market. It’s flexible, efficient, and if you can’t earn enough money to survive, it’s your own fault. But, this looks a lot different when you start to see capitalism as system of an unaccountable minority on top, driven by greed, stealing from the very people who made them wealthy, and using the money to change legislation, and undermine democracy in order to further concentrate their own wealth.

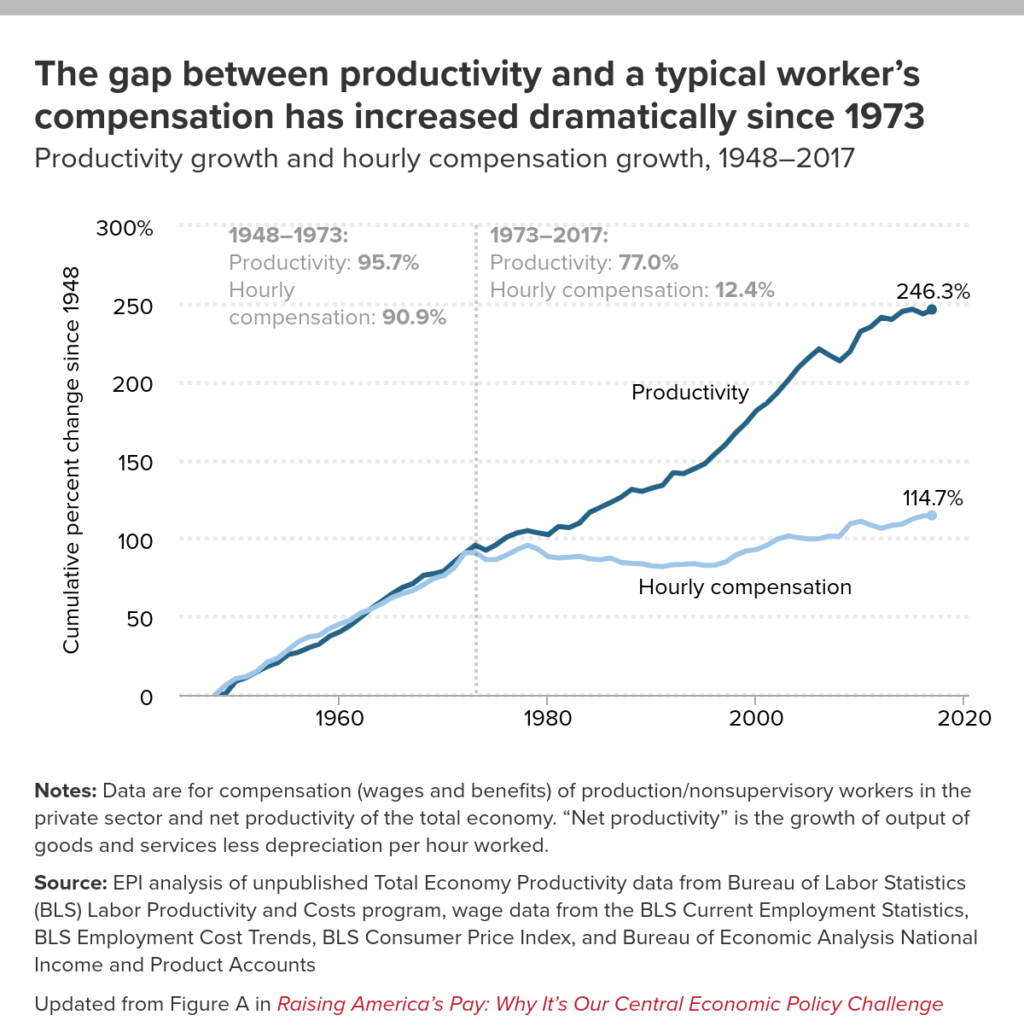

Is this theory true? Well, if the labor theory of value is true, we would be able to see a divergence between productivity and compensation, because the people producing the value would not be getting it. Let’s check:

Socialism

Karl Marx first articulated the Labor Theory of Value as a system in which surplus value is actually taken from the person producing it. Socialists take a look at the material input and the labor input, and recognize that it is a buildup of human labor that no one person has a right to control.

Since the workers and the capitalist both brought value to the product that is being sold: one put in the material half, and the other added the labor, socialists believe that it is only fair (and in the best interest of society, anyway) that everyone who had a share in producing the final product should have a say in how it is used.

The “abolition of private property” and “collective ownership over the means of production” essentially just means that we believe the workplace should be run democratically. The company as a whole should hire and fire their managers, set wages, arrange benefits and goals, and determine how to increase profits. One person or a small group of people should not be allowed to suck wealth out of people who have no choice but to continue producing it in exchange for a bare existence.

W. E. B. DuBois said of democracy, “the best arbiters of their own welfare are the persons directly affected.” Workers will not vote to give power back to a tiny minority. They will not vote for pitiful wages or non-existent benefits. They will not vote to outsource their own jobs or work grueling hours.

Socialism is the belief that we should build a society based on worker self-management or “collective ownership,” mutual aid, and the basic principle that everyone is equal and has an equal right to exist.

What’s more: we see socialism as an urgent necessity. Capitalism is not equipped to deal with so-called “externalities,” that is, social consequences of an exchange that are not reflected in the cost of goods or services that are being produced and traded. Climate change is one such externality.

The global climate crisis is a threat to human existence, and we only have about a decade before we begin dealing with the repercussions in a very tangible way. As long as we live in a society driven by personal gain, the looming threat of human extinction will remain a mere footnote in our priorities.

Seize the means of production.